175 years after Seneca Falls, what Equal Rights Amendment mean to the 21st Century

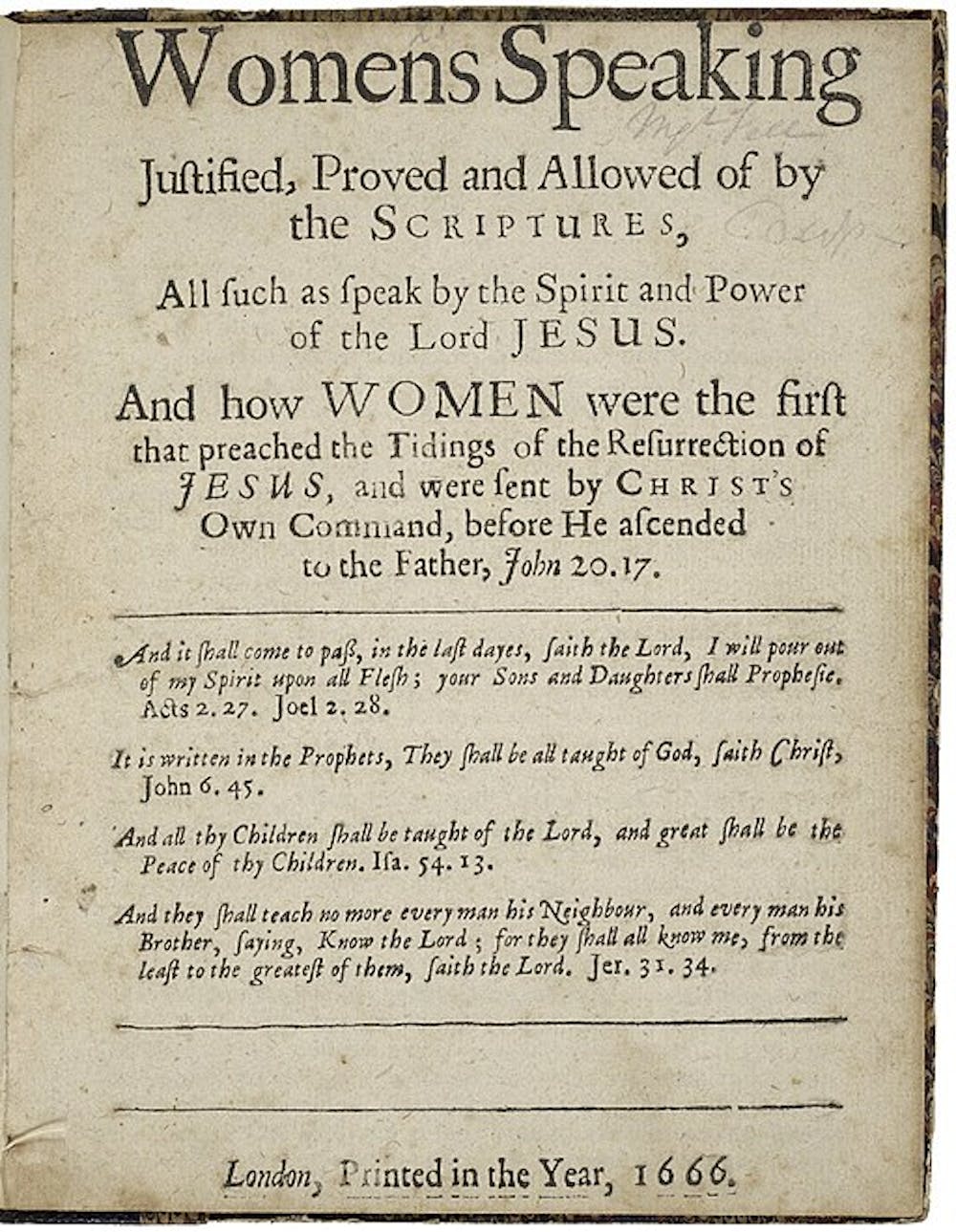

Folger Shakespeare Library/Wikimedia Commons. Photo Credit Folger library

“Shall we behold, unheeding,

Life’s holiest feelings crush’d?–

When woman’s heart is bleeding,

Shall woman’s voice be hush’d?”

Elizabeth Margaret Chandler

In 1848, nearly 300 men and women gathered in Seneca Falls, New York, to begin the United States’ first public political meeting regarding women’s rights. Seneca Falls Convention resulted in the Declaration of Sentiments, a document modeled on our Declaration of Independence that asserted “all men and women are created equal.” Now, 175 years after Seneca Falls, what would an Equal Rights Amendment mean to the 21st Century? How are we still cultivating radical feminist leadership among Friends today? Where did their politics come from?

The Seneca Falls Convention marked the beginning of the movement for women’s suffrage. Women’s Rights would first be granted 70 years later by the ratification of the 19th Amendment of the Constitution. It likely wouldn’t have happened without women Quakers. Four of the convention’s five leaders belonged to the Religious Society of Friends, whose ideas and community deeply shaped the meeting. Testimony of Equality for Friends means that all men and women possess an “inward light” – a light of Christ – and are therefore equal in the eyes of God. This testimony has led Quakers to recognize women as spiritual leaders from our earliest days, distinguishing Friends from many other religious groups from the time of the early suffragist movement.

The Quaker leaders at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 were Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Martha Coffin Wright, Jane Hunt, and Mary Ann McClintock. These women were all married mothers. Quaker women who participated in gathering at Seneca Falls had been nurtured in a Friends’ religious community that historian Nancy Hewitt describes as a “rich female world of faith, family, and friendship” – one that led many to step into public sphere and work for social reforms. Differing political views of Stanton and Mott were touchstones that eventually developed into consensus. Suffrage was not inevitable. It was also not a movement without push back and ‘fits and starts.’ For example: the New Jersey Assembly passed a law in 1797 to create women’s rights to the vote. However, the 1797 voting law, recognizing the right of women to vote across the state wasn’t forever,. New Jersey women voted in large numbers until 1807. Then the Assembly passed a new law limiting suffrage to ‘free white males.’ With this example, one can see how women’s right, like other human and political rights, is often attached to other oppression like racism. To read more about the history of history of suffrage, consider visiting Rutgers University suffrage history here.

A new Suffrage Anthem

Let us honor suffrage wisdom, embrace their call,

For a world that’s resilient, thriving with justice for all.

Through collaboration, innovation, and mindful living,

We’ll create more equal futures that are truly worth giving.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton is another important person to consider when looking at the way women’s; rights have developed in the United States. Stanton is credited along with Mott and other Quaker women as being the force that led the rapid growth and evolution of women’s’suffrage 175 years ago.

Queries: How can equality between sexes grow into political reality today? Can equality be felt ‘living in the world but not of the world’ if we do not recognize equal rights also under law? How can South Jersey Quakers support S.J. Res. 5, to immediately revive consideration of an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which needs ratification by only three new states to ensure our Constitution finally guarantees full and equal protections to women? What is ours to do?

Leave a Reply